The News Editorial Analysis 22nd Dec 2021

New chief of BrahMos

Eminent scientist AtulDinakarRane was appointed Director General, BrahMos, DRDO, and CEO and MD BrahMos on Monday. Mr. Rane has significantly contributed to the missile programmes and was a core member during the foundation of the Brhamos Aerospace. A graduate from Guindy Engineering College, Chennai, he did his PG in guided missiles from the University of Poona and joined the DRDO in 1987 and has worked in various capacities in the Defence Research and Development Laboratory (DRDL) and Research Centre Imarat (RCI) here, said a press release.

Award for NGRI scientist

Senior principal scientist at CSIR-National Geophysical Research Institute, Abhey Ram Bansal has been selected for the prestigious AnniTalwani Memorial Prize-2021 by the Indian Geophysical Union (IGU). The award will be given during the 58th annual convention of IGU at Shillong in February next year. Mr. Bansal has carried out significant research work on earthquake triggering, hydrocarbon exploration and geothermal studies.

Thinking before linking

Despite progressive aspects, linking electoral rolls with Aadhaar raises apprehensions

An unwillingness to allow meaningful debate and invite wider consultation can undo even the progressive aspects of problematic legislation. Ignoring protests, the Union government has managed to push through a Bill in Parliament to link electoral roll data with the Aadhaar ecosystem. On the face of it, the Bill’s objective — to purify the rolls and weed out bogus voters — may appear laudable, and the seeding of Aadhaar data with voter identity particulars may seem to be a good way of achieving it. Indeed, this can also allow for remote voting, a measure that could help migrant voters. The four qualifying dates for revision of rolls will help in faster enrolment of those who turn 18. However, other aspects hold grave implications for electoral democracy. The Opposition underscored the possible disenfranchisement of legitimate voters unwilling or unable to submit Aadhaar details, the possible violation of privacy, and the possibility that demographic details may be misused for profiling of voters. Each is a valid concern that ought to be considered by a parliamentary committee. Union Law Minister KirenRijiju has said the proposal has been unanimously approved by the Parliamentary Committee on Law and Justice. But, it is not clear if the specifics of the Bill had been discussed widely and public opinion sought.

There are indeed complaints that some electors may be registered in more than one constituency and that non-citizens have been enrolled, but these can be addressed by other identification processes. In fact, the Aadhaar database may be irrelevant to verify voter identity because it is an identifier of residents and not citizens. And the complaints of wrongful enrolment have come up even against the unique identity number allotted to more than 90% of the population. Mr. Rijiju is confident that the Election Laws (Amendment) Bill satisfies the tests laid down by the Supreme Court — a permissible law, a legitimate state interest and proportionality. However, this has to be rigorously examined. Even though the Aadhaar requirement is said to be voluntary, in practice it can be made mandatory. The Bill says the election registration officer may require the submission of the Aadhaar number both for new enrolments and those already enrolled. The choice not to submit is linked to a “sufficient cause”, which will be separately prescribed. Whether the few permissible reasons not to intimate one’s Aadhaar number include an objection on principle is unknown. If an individual’s refusal to submit the detail is deemed unacceptable, it may result in loss of franchise. Therefore, the measure may fail the test of proportionality. If the Government really has no ulterior motive in the form of triggering mass deletions from the electoral rolls, it must invite public opinion and allow deeper parliamentary scrutiny before implementing the new provisions that now have the approval of both Houses of Parliament.

A foul cry

Neither vigilantism nor disproportionate punishment are answers to ‘sacrilege’

In a disturbing sequence of events, two men were beaten to death over alleged attempts to “commit sacrilege” in the sanctum sanctorum of the Golden Temple in Amritsar and on the Sikh flag in a gurudwara at Nijampur village in Kapurthala earlier this week in Punjab. With passions now running high as the State heads to polls early next year, political parties have jumped into the fray seeking tougher laws and alleging conspiracies. Prominent political leaders cried foul over the alleged attempts at committing sacrilege, but few questioned the murders of the alleged perpetrators without even investigating their crimes. The use of vigilantism as retaliation for their alleged acts is clearly illegal but it is also deeply problematic in other ways as it has disallowed any possibility of unravelling why these incidents occurred and if they were attempts to foment communal tensions. In the Nijampur incident, the police have said the unidentified man who was lynched by sewadars at the gurudwara was most likely a thief, which suggests that the police must book those who took the law into their own hands. Upholding law and order is paramount in defusing tensions related to inflamed religious passions and, unfortunately, the proximity of elections seems to deter this possibility.

The rabble-rousing State Congress chief, Navjot Singh Sidhu, for example, upped the ante by seeking a “public hanging” for those convicted of crimes of committing sacrilege. Earlier in 2018, the State cabinet had sought to pass amendments to the Indian Penal Code (IPC) seeking life imprisonment for those convicted of committing sacrilege against the holy books of major religions, a problematic proposal that sought punishment far disproportionate to the crimes. The proposal itself was redundant as the Supreme Court clarified that Section 295A of the IPC “punishes the aggravated form of insult to religion when it is perpetrated with the deliberate and malicious intention of outraging religious feelings”. Besides, if invoked, it could be used to jail miscreants for up to three years. It is a Section misused to prosecute people in the name of protecting the sentiments of sections of society, thereby dampening freedom of expression. Seeking extraordinary punishment for crimes that are vaguely defined such as “sacrilege” would be an even more retrograde step as the application of stringent “blasphemy laws” elsewhere has shown. The State must now allow the police to conduct thoroughgoing inquiries. It must also bring to justice those engaged in vigilantism. Meanwhile, political parties committed to peace in the State must seek to defuse any public anger over the alleged acts of “sacrilege” and not let it descend into communal

How the Code on Wages ‘legalises’ bonded labour

It allows employers to extend unlimited advances to workers and charge an unspecified interest rate on such loans

Debt bondage is a form of slavery that exists when a worker is induced to accept advances on wages, of a size, or at a level of interest, such that the advance will never be repaid. One of India’s hastily-passed Labour Codes — the Code on Wages, 2019 — gives legal sanction to this horrifically repressive, inhuman practice, by allowing employers to extend limitless credit advances to their workers, and charge an unspecified (and hence, usurious) interest rate on them.

Despite previously existing legal protections, vulnerable agricultural, informal sector and migrant workers were already becoming trapped in a vicious cycle of mounting debt and dwindling income, stripping them, their families and future generations, of their most basic rights. It remains one of the most pernicious sources of control and bondage in India, and is incompatible with democracy.

What is shocking is that instead of preventing such enslavement of workers and protecting their fundamental rights, the present government appears to openly abet the practice, by undoing even the weakest safeguards earlier in place under the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 (now subsumed in the Code).

A free pass to debt bondage

Rule 21 of the Minimum Wages (Central) Rules, 1950 (corresponding to the Act) spelt out certain ‘deductions’ permissible from the wages of workers. The sub-rule (2)(vi) allowed for “deductions for recovery of advances or for adjustment of over payment of wages, provided that such advances do not exceed an amount equal to wages for two calendar months of the employed person”.

Additionally, it stated, “in no case, shall the monthly instalment of deduction exceed one-fourth of the wages earned in that month”.

Compare this with Section 18(2)(f)(i) of the Code on Wages, which introduces two major changes to the foregoing.

This section allows deductions from wages for the recovery of “advances of whatever nature (including advances for travelling allowance or conveyance allowance), and the interest due in respect thereof, or for adjustment of overpayment of wages”.

The subtle manipulations introduced have huge implications. One, it has done away with the cap of ‘not more than two months’ of a worker’s wages under the earlier Act, that an employer can give as advance. This allows employers to lend unlimited advances to their workers, tightening their grip.

Two, it has legalised the charging of an interest rate by the employer on such advances, by adding the clause on interest, and with no details on what might be charged. The net impact is an open sanction for the bonded labour system to flourish.

Moreover, the Code increases the permissible monthly deduction towards such recovery, up to one-half of the worker’s monthly wage, as compared with one-fourth under the earlier Act.

Not that the presence of any law under our Constitution even before the Labour Codes — such as The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 — or various Supreme Court judgments, have ever deterred the bonded labour system from being widespread across sectors, from agriculture to quarrying, spinning, and more.

Cases in Rajasthan

In Baran district, Rajasthan (2011-12), a series of Sahariya (a primitive tribal group) families boldly came out one after the other and spoke of their harrowing experiences of violence and even rape at the hands of Sikh, caste Hindu, and Muslim landlords, for whom they had worked as ‘halis’ for generations. The mostly upper-caste government officials from the Collector onwards put up a wall of resistance in acknowledging them as bonded labourers as per the Act, thereby denying them any sort of relief or rehabilitation, till pressure was mounted.

In a large-scale primary survey in a mining cluster of Nagaur district, Rajasthan for the Mine Labour Protection Campaign (2015), we found that one in three workers interviewed had taken advances from their employers ranging from ₹1,000-₹1,50,000 at the time of joining work. Of them, about 50% said they took the amount “to pay off the earlier employer or a moneylender”.

But in Parliament, the existence of bonded labour has simply been denied among elected representatives, or grossly understated.

Debt bondage and forced labour flourish because the Government has done nothing to ensure the economic security of labourers. And it is set to worsen if this labour code provision is allowed to take shape.

Need for state intervention

It is no coincidence that the disproportionate effect of this huge regression in the Labour Code will fall on Dalits and the landless. In the Nagaur study, for instance, we found that 56% of the workers were Dalits, as contrasted with only 3% of the mine owners.

The vast proportion of landless agricultural labourers in India, to date, areDalits.

AnandTeltumbde powerfully writes in Republic of Caste, “The dominant castes understood that if dalits came to own the means of survival, they would repudiate their servile status and its attendant social bondage… Economic independence is an aspect of liberty and its absence, as a corollary, spells slavery.”

Indeed, this is exactly what B.R. Ambedkar feared would play out in India, and hoped to prevent, through his pamphlet, States and Minorities, released in the 1940s (see Article 2). In her Ambedkar Lecture, 2018 at the University of Edinburgh, RupaViswanath, Professor of Indian Religions at the Centre for Modern Indian Studies, University of Göttingen, expounds on Ambedkar’s later-age line of reasoning that “what makes the translation of ‘one-man-one vote’ to ‘one-man-one-value’ possible, is the worker’s economic freedom”.

Ambedkar understood that economic enslavement was an extreme form of coercion that rendered political freedom meaningless, and that democracy itself required state intervention in the economic structure to prevent such practices, she says.

While he proposed a complete recast of rural and agrarian land structures, and state ownership of land as crucial to this, she explains, he also defined democracy as resting on two premises that required the existence of economic rights.

The first, relevant to the present discussion on Labour Codes, was that “an individual must not be required to relinquish his Constitutional rights as a condition precedent to the receipt of any privilege”. But that is exactly what the unemployed are forced to do — merely for the sake of securing the ‘privilege’ to work and to subsist, she notes.

Deepening inequality

The larger picture we must keep in mind, therefore, is this. Government after government, under the garb of being pro-worker, has schemed to intervene in exactly the opposite direction as desired — by maintaining and deepening economic inequality to the advantage of the privileged castes and classes, thereby keeping true political freedom out of the workers’ reach. And it is this line that the Central government has pursued with even more gusto, in the recasting and passing of these retrogressive labour codes.

If the farm laws could be repealed, then these anti-labour codes, with numerous other dilutions that snatch away the mostly non-existent rights of the far more vulnerable class of workers, must surely go.

Compassionate job not a vested right, says SC

The Supreme Court has held in an order that compassionate employment is not a vested right. A Bench of Justices D.Y. Chandrachud and A.S. Bopanna said the compassionate employment scheme was intended to enable a bereaved family tide over financial crisis caused by the untimely death of a breadwinner while in service.

“Compassionate appointment is not a matter of right, but is to enable the family to tide over an immediate crisis which may result from the death of the employee,” the court noted. It said the authorities were allowed to use their discretion to evaluate the financial position of the family. “Undoubtedly, pension is not an act of bounty, but is towards the service which has been rendered by an employee. However, in evaluating a claim for compassionate appointment, it is open to the authorities to evaluate the financial position of the family upon the death while in service,” the Supreme Court has observed.

The court was hearing an appeal filed by the Union government against a Madras High Court judgment which upheld a Central Administrative Tribunal direction to consider the compassionate appointment of the widow of a sergeant in the Air Force, who had died of cancer in 2008.

NATO seeks ‘meaningful’ talks with Russia early next year

Putin hints at ‘military-technical measures’ against actions

NATO will seek meaningful discussions with Moscow early next year to address tensions amid a Russian military build-up on Ukraine’s border, alliance Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said on Tuesday.

“We remain ready for meaningful dialogue with Russia and I intend to call a new meeting of the NATO-Russia Council as soon as possible in the new year,” Mr. Stoltenberg told a news conference in Brussels.

Mr. Stoltenberg, however, made it clear that it was solely up to NATO and Ukraine to decide about a future membership of Kyiv.

Meanwhile, President Vladimir Putin warned on Tuesday that Russia was prepared to take “military-technical measures” in response to “unfriendly” Western actions over the Ukraine conflict.

Mr. Putin told defence ministry officials that if the West continued its “obviously aggressive stance”, Russia would take “appropriate retaliatory military-technical measures”.

“If this infrastructure moves further — if U.S. and NATO missile systems appear in Ukraine — then their approach time to Moscow will be reduced to seven or 10 minutes,” he said. Despite hinting at conflict, Mr. Putin said that Russia wants to avoid “bloodshed”.

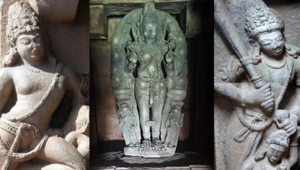

The plight of Tamils of Indian origin in Sri Lanka

In a highly commendable move, the Rajapaksa brothers, who hold the reins of power in Sri Lanka, invited the UN Human Rights Council dealing with contemporary forms of slavery to visit Sri Lanka, study the living conditions of the most exploited sections of society like people working in garment firms in export promotion zones, tea plantation workers and migrants. Sri Lanka is the first country in South Asia to take this imaginative initiative. Will other countries in the region emulate the Sri Lankan example?

TomoyaObokata, UN Special Rapporteur, visited Sri Lanka between November 26 and December 3 for an on-the-spot study of the problems and met a cross section of workers, government officials, trade union leaders and NGOs involved in the subject. The rapporteur presented the preliminary findings in a meeting held on November 26. The final report would be submitted to the UN in September 2022.

The workers in the tea plantations are of Indian Tamil origin. Apply any yardstick—per capita income, living conditions, longevity of life, educational attainments and status of women—they are at the bottom of the ladder. The UN Special Rapporteur has highlighted: “Contemporary forms of slavery have an ethnic dimension. In particular, Malaiyaha Tamils—who were brought from India to work in the plantation sector 200 years ago—continue to face multiple forms of discrimination based on their origin.”

In 2017, Sri Lanka celebrated the 150th anniversary of its tea industry. The government and the planters organised a number of seminars and conferences to highlight the role of the tea industry in the economy, how to increase production in the sector and how to modernise it. The Institute of Social Development in Kandy was the only organisation that convened a seminar on those who produce the Two leaves and a Bud (novel written by Dr Mulk Raj Anand) that brings cheer early in the morning to millions across the world.

The contrasting lives of the planters and workers should be highlighted. Given below are two quotations that describe the contrast. The BBC, in 2005, telecast a documentary titled How the British Reinvented Slavery. The documentary portrays the lives of the planters as follows: “You can sit in your veranda, and sip the lemonade and be fanned by a servant and have your toenails cut at the same time by some coolie, and you can watch your labourers working, you could sleep with any woman you wanted, more or less everything was done for you from the time you wake up and the time you went to bed. People looked after you, people obeyed you, people are afraid of you, your single word as a plantation owner could deny life.”

Vanachirahu, a young poet from Malaiyaham, gave expression to the innermost feelings of his people in times of communal troubles. In a poem titled Dawn, the poet writes: “Our nights are uncertain, dear, let us look at each other, before we go to bed. This may be our last meaningful moment. Finally press your lips on the cheeks of our children. Then let us think about our relatives for a moment. Lastly let us wipe our own tears.”

The most important feature of the Malaiyaha Tamils is the sharp decline in their population. At the time of independence in 1948, they were more in number than Sri Lankan Tamils. Because of the two agreements signed in 1964 and 1974 between Colombo and New Delhi, and repatriation of a large number of people as Indian citizens, their number declined. Today, according to census statistics, they number only 5.5% of the population.

For the first few decades after independence, the major problem confronting the Indian Tamil population was the issue of statelessness. With a judicious mix of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary struggles, the community, under the leadership of SavumiamoorthyThondaman, was able to extract citizenship rights from a recalcitrant Sinhalese-dominated government. All those born in Sri Lanka after October 1964 were granted citizenship, which also included the residue of the Sirimavo-Shastri pact, yet to be repatriated to India. With the introduction of the proportional system of representation under the 1978 Republican Constitution, the community was able to send more representatives to Parliament.

The community is now engaged in a struggle for equality and dignity. The living conditions are improving but much more remains to be done before they can enjoy the status of perfect equality. First and foremost, human rights violations continue to take place. Though the political parties representing the Malaiyaha Tamils never subscribed to the demand for a separate state, they were subjected to vicious and savage attacks by lumpen sections of Sinhalese in 1977, 1981 and 1983. I happened to be in Hatton after the Bindunewa massacre in 2006. Indira, a young lady, confided that she was scared to move around Hatton because of insecurity. She contrasted that to her life with her brother in Perambur, Chennai, where she could go without any fear for late-night film shows. Second, the tea workers’ daily wage is around 1,000 Sri Lankan rupees, which is not even sufficient to meet their daily needs. Many, therefore, absent themselves from the plantations and go to work in vegetable farms where they are able to get double the wages, in addition to breakfast and lunch. Finally, while every boy and girl goes to school, there are many dropouts. Very few enter the university level. I was associated with the University of Peradeniya as a SAARC Professor for International Relations in 2006. In the final-year BA class, in Tamil medium, there were 10 students, of whom eight were Muslim girls, a boy was from Batticaloa and a girl from the plantation area. In the same year, the number of teachers from the Indian Tamil community in the university was less than 10.

In his plan of action for three years, Sri Lankan High Commissioner MilindaMoragoda has highlighted that there should be more educational exchanges between the two countries. For instance, the Chennai Centre for Global Studies is very keen to step into the scene and assist the Tamil children, especially from the hill country, to come to India for secondary and college education, and is prepared to meet all their expenditures and also offer them scholarships. The community can come up only if they have good value-based education. Tamil Nadu can play a benign role in this direction.

The transformation from Thottakattan (barbarian from the plantations), a contemptuous term used by Jaffna Vellalars, to the noble appellation Malaiyaha Tamil is an illustration of the qualitative change that has taken place in the hill country. But much more remains to be done before they become equal citizens enjoying equality of opportunity.

Let me conclude with a poem written by M ANuhman whom I had the privilege to know at the University of Peradeniya: “Where there is no equality, there is no peace, where there is no peace, there is no freedom, these are my last words, equality, peace and freedom.”

No central record of anti-national cases, no such word in statute: Government

The word ‘anti-national’ finds no mention in the Constitution. However, it was once inserted in the Constitution during Emergency in 1976 and later removed, Union Minister of State for Home NityanandRai informed LokSabha on Tuesday.

Rai was responding to a question by Hyderabad MP AsaduddinOwaisi, who asked whether the government had defined the meaning of ‘anti-national’ under any legislation or 11 rules or any other legal enactment enforced in the country.

Owaisi also asked whether the Supreme Court had prescribed any guidelines to deal with crimes relating to ‘anti-national’ activity. In a written reply, the Deputy Home Minister said: “The word ‘anti-national’ has not been defined in statutes. However, there are criminal legislations and various judicial pronouncements to sternly deal with unlawful and subversive activities which are detrimental to the unity and integrity of the country.”

In his response, the minister of state for home said it was relevant to mention that the Constitution (42nd Amendment) Act, 1976 inserted in the Constitution Article 31D (during Emergency) which defined ‘anti-national activity’ and this Article 31D was subsequently, omitted by the Constitution (43rd Amendment) Act, 1977.

Owaisi also sought details of the number of people arrested for indulging in ‘anti national’ activities in the last three years. Rai said the statistics about the number of people arrested for indulging in anti-national activities was not maintained centrally. He said the responsibility of maintaining law and order rested primarily with the respective state government.

“The responsibility of maintaining law and order, including investigation, registration and prosecution rests primarily with the respective state governments,” the minister said.

The News Editorial Analysis 21st Dec 2021