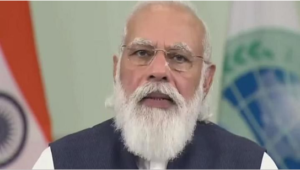

PM launches mega health infra mission, slams previous govts.

ACCUSING PREVIOUS governments of neglecting healthcare, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Monday launched the nationwide Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission, which he said will strengthen health infrastructure, right from the village level, in the next four or five years.

“All this work should have been done decades ago,” Modi said, launching the Rs 64,000 crore mission in Varanasi, his Lok Sabha constituency.

Earlier in the day, inaugurating nine medical colleges in Sidharthanagar district, the Prime Minister targeted the previous Samajwadi Party government in the state. He said it failed to provide facilities to the poor but “Bhrastachar ki cycle” or cycle of corruption kept moving 24 hours and nepotism flourished.

Launching the heath mission, along with development projects worth around Rs 5,200 crore for Varanasi, Modi said health infrastructure in the country did not get the required attention for a long time after Independence and the people suffered. He said previous governments deprived the people of healthcare facilities, adding that the mission would plug this gap. Giving details, he said two aspects of the mission are creation of facilities for diagnostics, and treatment by opening Health and Wellness Centers in villages and cities. He said 35,000 new critical care-related beds will be added in 600 districts, and free consultation, tests and medicines would be provided. The third aspect of the mission, he said, would be expansion of research institutions that study pandemics. This will help prepare for future pandemics. “It is a part of the effort to achieve holistic healthcare,” he said.In Sidharthanagar district of Purvanchal, Modi praised the Yogi Adityanath government as he targeted the Samajwadi Party, taking jibes at its poll symbol cycle. “The current governments at Centre and in Uttar Pradesh are the result of decades of hard work of several Karma Yogis,” he said.

“The government that was there in Delhi seven years ago and the one in UP four years ago, what did they do for Purvanchal? Those who were there in the government in the past, they used to announce opening of dispensaries or small hospitals and people used to become hopeful. But for years either the building was not constructed, or if the building was there, machines were not there. And if both were there, doctors or staff were not there.” To top it all, he said, “The cycle of corruption that looted crores of rupees of the poor continued to run 24 hours.”

The tumult next door.

India must pay greater attention to its most difficult neighbour

For Delhi, the current crisis in Pakistan is not a moment for schadenfreude. It should be an occasion to reflect on the long-term regional consequences.

As multiple crises in Pakistan come to a head, can Delhi remain a mute spectator forever? In most other countries of the subcontinent, India is drawn quickly into their internal political arguments. Delhi has always exercised some influence on the outcomes of those contestations. But Delhi has rarely been a decisive player in Pakistan’s internal politics. India’s intervention in 1971 to liberate Bangladesh — the 50th anniversary of which is round the corner — was an exception rather than the rule. Whether it can or should make a difference to Pakistan’s internal politics, India must pay greater attention to the internal dynamics of our most difficult neighbour and more purposefully engage a diverse set of actors in that polity. This is not the place to get into the rights and wrongs of India’s interventions in the internal affairs of its other South Asian neighbours. It is enough to note that India’s interventions are a recurring pattern in the subcontinent’s international relations. Even when Delhi is reluctant to get into the weeds of these conflicts, the competing parties in the neighborhood demand India’s intervention on their behalf. All of the contestants, of course, resolutely oppose India’s meddling when it goes against them. If Delhi’s interventions are part of South Asian political life, why is Pakistan such an exception? Delhi’s hands-off attitude is surprising, given India’s huge stakes in the nature of Pakistan’s policies and their massive impact on regional security. Delhi is hesitant to articulate even basic interests in Pakistan in general terms, let alone take sides in its internal politics.

Indian media, which is so obsessed with covering the disputes with Pakistan, has no time for the internal politics next door. It hardly spends any resources covering the turmoil within Pakistan. India’s political classes too seem utterly disinterested in Pakistan’s domestic developments. For Delhi, it is always about narrow political arguments with Rawalpindi and Islamabad; it is as if the people of Pakistan do not exist. This indifference is also rooted in profound pessimism — that Pakistan will never change and that there is little Delhi can do about it. The depth of the current crises in Pakistan, however, should nudge India into overcoming this entrenched indifference. Delhi can’t forget that change is an immutable law of nature and that Pakistan is not immune to it. Among the many challenges confronting Pakistan is the fresh breakdown in civil-military relations as Prime Minister Imran Khan bites the hand that has nurtured his rise to power. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s economy is in a tailspin as it struggles to negotiate a stabilisation package with the International Monetary Fund. The militant religious movement Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) has mounted a fresh march against the capital demanding the release of its arrested leader, Saad Rizvi. Meanwhile, a coalition of opposition parties is stepping up protests to highlight the economic misery of the people; it is betting that the Imran Khan government can be pulled down well before it completes its full term two years from now.

The internal crises are sharpened by worsening external conditions. In Afghanistan, Pakistan has succeeded in restoring the Taliban to power. The celebrations have not lasted too long; the long-awaited victory is turning sour. The Arab Gulf states that have been fast friends of Pakistan are now tilting towards India. Once a favorite partner of the West, Pakistan today faces tensions in its ties with the US and Europe.

More broadly, nuclear weapons and a powerful army seem unable to stop Pakistan’s relative decline in relation to not just India but also Bangladesh. Pakistan’s economy is now 10 times smaller than that of India and is well behind Bangladesh. This trend line is unlikely to change in the near future.

A reference to these crises could easily be dismissed as wishful thinking from Indian analysts. Even the sincerest well-wisher of Pakistan, however, can’t miss the country’s dangerous downward trajectory.

For India, this is not a moment for schadenfreude. It should be an occasion to reflect on the long-term regional consequences of Pakistan’s internal turbulence. Many in Delhi would dismiss the cause for such concern. They would point to Pakistan’s survival skills. After all, Pakistan’s journey since independence has been a dangerous one marked by unending near-death situations. Pakistan has certainly endured.

Some would point to Pakistan’s enormous political luck in finding external patrons eager to bail it out for geopolitical reasons. While the US and Saudi Arabia have done this in the past, they don’t appear as enthusiastic today.

Some would continue to bet that China could still save its all-weather friend Pakistan from hurtling down the abyss. Until now at least, the Chinese seem tight-fisted in comparison to the West, which was generous to a fault when it came to Pakistan. There is also a growing frustration among Islamabad’s friends that there is little that they can do if the Pakistani state has no will or capability to get its act together.

The key to Pakistan’s near future may lie in the manner in which the current tensions between Army Chief General Qamar Jawed Bajwa and PM Khan are resolved.

Problems between the army and the political leaders have indeed been endemic in Pakistan’s history. They acquired a particular intensity in the last few years as the previous prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, sought to assert himself on key issues relating to Pakistan’s support for Islamic militants.

The army hounded Nawaz Sharif out of power and in the elections that took place in 2018, it installed Imran Khan as the prime minister by stitching together a majority coalition for his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). It was widely assumed that the deal between the army and Imran Khan would bring stability and efficiency to policy-making in a badly-governed Pakistan.

For once the army had someone different from the jaded mainstream politicians to work with. Imran’s popularity with the younger generation and his promise to create a Naya Pakistan seemed just the right formula, one that the army needed. Three years later, this so-called hybrid regime is in tatters and civil-military relations are back in crisis mode. This round began earlier this month with the army announcing several transfers of four-star generals, including the ISI Chief General Faiz Hameed. But Imran Khan has been reluctant to let the ISI chief go. What should have been a routine change has now become a battle of wills between General Bajwa and Premier Khan. Imran has made bold to challenge the paramount authority of the army chief. While the GHQ is quite capable of pulling down the Imran government, the PM is turning to religious mobilisation to secure his flanks. How this plays out will be of special interest to Delhi. Sceptics will, however, say the differences within the Pakistani establishment on the policy towards India are tactical and, therefore, not consequential.

Realists might concede that unlike elsewhere in the neighborhood, Delhi’s leverage in Pakistan’s politics is terribly limited. But it is by no means negligible. After all, India looms so large in Pakistan’s mind space. For Delhi, it may be worth trying to turn that into influence over Pakistan’s policies if only at the tactical level and at the margins.

BSF jurisdiction: parties in Punjab oppose Centre’s decision.

The move came following an all-party meeting convened by Punjab Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi here on Monday to deliberate on the issue of jurisdiction of the Border Security Force. The Punjab BJP boycotted the meeting.

All political parties except the BJP have decided to reject the Centre’s notification of extending the jurisdiction of the BSF by calling a special session of the Punjab Assembly.

The move came following an all-party meeting convened by Punjab Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi here on Monday to deliberate on the issue of jurisdiction of the Border Security Force.

The meeting also resolved to strongly oppose the Centre’s decision “constitutionally, legally and politically” in order to restore the status quo that existed before the notification of October 11, 2021.

The Punjab unit of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) boycotted the meeting.

Representatives of the Shiromani Akali Dal, Aam Aadmi Party, Lok Insaaf Party, SAD (Sanyukt) and other parties attended the meeting.The Union government had recently amended the BSF Act to authorise the border guarding force to undertake search, seizure and arrest within a 50 km stretch, up from the existing 15 km, from the international border in Punjab, West Bengal and Assam.

Addressing reporters, Channi said the meeting was held in a conducive atmosphere and representatives of the political parties passed a resolution that the notification which extended the BSF’s area of operation should be rejected.

By calling the Vidhan Sabha session, all (the parties) will jointly reject the notification. All parties are unanimous on it,” Channi said while thanking representatives of all the parties for their complete support in the ‘yagya’.

Channi further said the government will also approach the Supreme Court over this matter.

Channi told the central government that the Punjab government was capable of securing the state while asserting that law and order was a state subject. He assured all political parties that the posts of chief minister and ministers do not matter to them before the interests of Punjab.

“We are ready to make any sacrifice but will not allow Punjab’s interests to be looted,” he said.

According to a resolution adopted at the meeting, “to maintain the law and order is the responsibility of the state government according to the Constitution and the Punjab government is fully competent for the same.”

“The central government’s decision to enhance the jurisdiction of BSF from 15 to 50 kms speaks of distrust and humiliation of Punjab police and its people,” it said.The state government would soon convene the special session of Punjab Vidhan Sabha on this sensitive issue and recommend to the Governor to hold the session at the earliest, Channi said.

Channi also asked political parties to make use of their good offices to prevail upon the non-BJP governments and other regional parties especially in the states of West Bengal and Rajasthan.

He said he would also take up this issue with his counterparts to mount pressure on Centre to roll back its decision which is a “direct onslaught” on the Centre-state relations.

Meanwhile, the chief minister said the Centre’s three “black” farm laws will also be rejected in the coming assembly session ..

When told that the Opposition was accusing him of agreeing to the extension of the BSF jurisdiction during his meeting with Union Home Minister Amit Shah, Channi rejected the charge and said he had raised several issues including the curbing of drugs smuggling from across the border.

Talking to the media, Punjab Congress leader Navjot Singh Sidhu accused the Centre of “weakening the federal structure by creating a state within a state.”

He called it a “political move” of the central government for its “vested interests” while questioning its timing as it comes just a few months ahead of the assembly polls.

The Punjab BJP, on the other hand, accused the Congress government of playing petty politics over the issue of national security.

Punjab BJP leader Manoranjan Kalia said the move of extending the BSF’s jurisdiction is meant to protect the national interests and stated that they had decided to boycott the all ..

In the meeting, SAD representatives called for a special assembly session to reject the centre’s decision and demanded that the Vidhan Sabha also set aside the three farm laws.

AAP Punjab president and MP Bhagwant Mann blamed the Channi-led government for the Centre’s move.

A moratorium on bottom trawling and support to the fishermen is a good first step towards a solution.

Context: Many Tamil Indian fishermen boats have been reportedly sunk due to collision with a Sri Lankan Navy patrol vessel after their reported crossing over of International Maritime Boundary Line, an invisible demarcation between India and Sri Lanka.

- Tamil Nadu fishermen’s associations have accused the Sri Lankan Navy of brutally attacking Indian fishermen. However, Sri Lanka has denied the allegations.

- New Delhi conveyed a “strong protest” to Colombo after the death of the four fishermen in January, allegedly at the hands of the Sri Lankan Navy. But there is no sign of a full inquiry since, let alone a credible one. The distressing incidents are neither peculiar to this year, nor inevitable.

Challenges:

- Unresolved conflict of the Palk Strait: The problem has existed for more than a decade now, from the time Sri Lanka’s 30 year-long civil war ended in 2009. That was when the island’s northern Tamil fishermen, who were displaced and barred access to the sea, began returning to their old homes, with hopes of reviving their livelihoods. This however posed a serious threat to the livelihoods of the existing Sri Lankan Tamil.

- Bottom Trawling: In Tamil Nadu, the wage of the fishermen working on mechanised fishing vessels used for ‘bottom trawling’ depends on the catch they bring back. Using the bottom trawling fishing method, they drag large fishing nets along the seabed, scooping out a huge quantity of prawns, small fishes and virtually everything else at one go. The practice, deemed destructive the world over but ensures sizeable profits for their employers. Fishermen enter Sri Lankan waters for better catch.

- Sri Lankan response: The Sri Lankan state’s response to the problem has been largely a military and legal one, tasking its Navy with patrolling the seas and arresting “encroachers”, banning trawling, and levying stiff fines on foreign vessels engaged in illegal fishing in its territorial waters. Little support has been extended to war-affected, artisanal fishermen in the Northern Province by way of infrastructure or equipment.

- Failure of talks: India and Sri Lanka have held many rounds of bilateral talks in the last decade between government officials as well as fisher leaders. The outcomes have mostly ranged from deadlocks, with Tamil Nadu refusing to give up bottom trawling, to template responses from the governments, with India seeking a “humanitarian response” from Sri Lanka.

- Resistance from boat-owners: The Indian government’s attempt to divert fishermen to deep sea fishing has not taken off as was envisaged, even as profit-hungry boat owners in Tamil Nadu stubbornly defend their trawler trade. It is evident that bottom trawling has maximised not only the profits made by vessel owners in Tamil Nadu, but also the risk faced by poor, daily wage fishermen employed from the coastal districts.

- Peril for Sri Lankan Fishermen: It is equally well known that the relentless trawling by Indian vessels has caused huge losses to northern Sri Lankan fishermen. Their catch has fallen drastically and they count vanishing varieties of fish. They are dejected as their persisting calls to end bottom trawling have not been heeded by their counterparts in Tamil Nadu “brothers”.

Urgent solution

- In 2016,a Joint Working Group was constituted to first and foremost, expedite “the transition towards ending the practice of bottom trawling at the earliest”.

- Viable substitutes: Such as subsidies on inland fisheries, making fishing in open seas unviable.

- Taking an Objective stand: Seeing the conflict merely through the prism of Tamil Nadu fishermen and the Sri Lankan Navy may not yield a solution to the problem, although that might keep its most deplorable symptom in focus.

- Tamil Nadu must consider a moratorium on bottom trawlingin the Palk Strait.

- Supporting Fishermen:both New Delhi and Colombo substantially supporting their respective fishing communities to cope with the suspension of trawling on the Tamil Nadu side and the devastating impact of the pandemic on both sides.

Conclusion: Strong bilateral ties are not only about shared religious or cultural heritage, but also about sharing resources responsibly, in ways that the lives and livelihoods of our peoples can be protected.

The Government’s objection to the methodology of the Global Hunger Index is not based on facts.

Context: The Global Hunger Index (GHI) report ranks India at 101 out of 116 countries, with the country falling in the category of having a ‘serious’ hunger situation. India’s standing has fallen from 94 (out of 107) in 2020.

- To add insult to injury, the GHI puts Indiafar below some of its neighbouring countries including Pakistan and Bangladesh. The government contends that the ranks are not comparable across years because of various methodological issues. However, it is true that year after year, India ranks at the lower end — below a number of other countries that are poorer in terms of per capita incomes. This in itself is cause for concern.

About Global Hunger Index (GHI): It is released annually by Concern Worldwide and Wealthungerilfe.

The GHI is ‘based on four indicators”

- Percentage of undernourished in the population (PoU)

- Percentage of children under five years who suffer from wasting (low weightforheight)

- Percentage of children under five years who suffer from stunting(low heightforage

- Percentage of children who die before the age of five (child mortality)’. The first and the last indicators have a weight of 1/3rd each and the two child malnutrition indicators account for 1/6th weightage each in the final GHI, where each indicator is standardized based on thresholds set slightly above the highest country level values.

Government’s objection to the methodology

- It says that it is based on Opinion Polls: They have based their assessment on the results of a ‘four question’ opinion poll, which was conducted telephonically by Gallup”, is not based on facts.

- Reality: The report is not based on the Gallup poll; rather, it is on the PoU data that the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) puts out regulations.

Various Worrying Trends

- Slow rate of progress: India has not been very successful in tackling the issue of hunger and that the rate of progress is very slow. Comparable values of the index have been given in the report for four years, i.e., 2000, 2006, 2012 and 2021. While the GHI improved from 37.4 to 28.8 during 2006-12, the improvement is only from 28.8 to 27.5 between 2012-21.

- A period before the pandemic: It must also be remembered that all the data are for the period before the COVID19 pandemic. There were many indications based on nationally representative data that the situation of food insecurity at the end of the year 2020 was concerning, and things are most likely to have become worse after the second wave.

- Disruption of government schemes: Services such as the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) and school midday meals continue to be disrupted in most areas, denying crores of children the one nutritious meal a day they earlier had access to.

- Ending of additional PDS entitlements: The only substantial measure has been the provision of additional free food grains through the Public Distribution System (PDS), and even this has been lacking. It leaves out about 40% of the population, many of whom are in need and includes only cereals. Also, as of now, it ends in November 2021.

- Budgetcuts: While we need additional investments and greater priority for food, nutrition and social protection schemes, Budget 2021 saw cuts in real terms for schemes such as the ICDS and the midday meal.

- Food inflation:inflation in other foods, especially edible oils, has also been very high affecting people’s ability to afford healthy diets.

Conclusion: There is no denying that diverse nutritious diets for all Indians still remain a distant dream

The News Editorial Analysis 26 October 2021